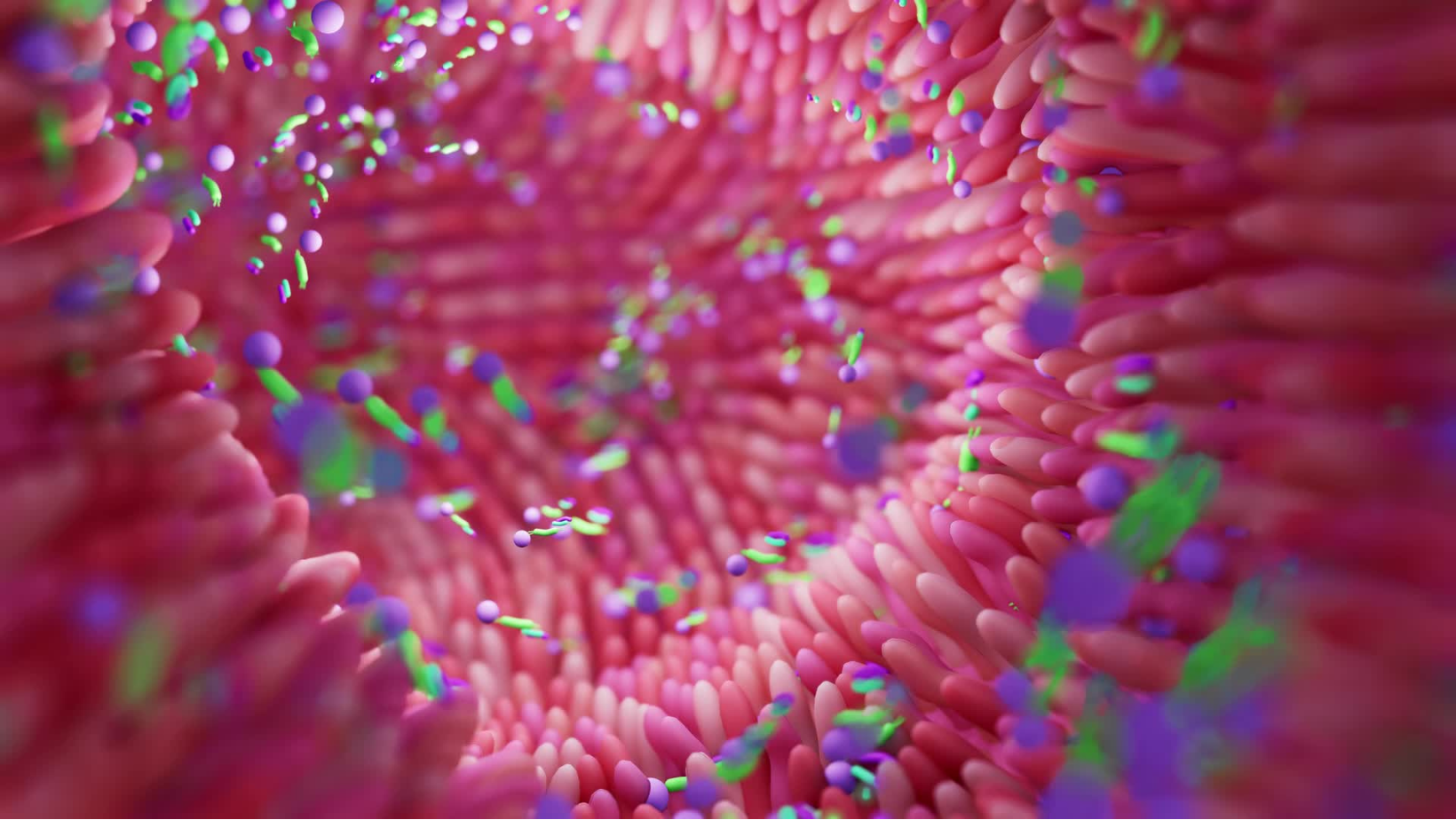

The microbiome is a vast community of microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses residing on and within the human body. Combined, these microbes possess more than 100 times the amount of genetic information than the human host that they are in relationship with. In turn, this genetic material corresponds to the functional roles of these microbes: what they metabolize, how they metabolize, and resulting products that are secreted in the body. Human body systems, such as the immune system, cardiovascular system, hormonal system, and nervous system, are affected by the combination of abundance and diversity of microbes; neurological and psychological health are intimately connected to the stability of these systems. It is also important to note that microbes and human hosts influence each other in a feedback loop; human genetics and environment play a critical role in which microbes thrive, and the interactions between microbes further affects functional impact.

Microbiome as Mediator

Describing a healthy microbiome is challenging because microbiome fingerprints, like other physiological profiles, are inherently unique to each person. In general, it is thought that a more diverse microbial profile provides ecological checks and balances, competing with one another to prevent pathogen dominance, aiding digestion and creating diverse metabolic products, and regulating the immune system. Microbial diversity can be optimized through proper nutrition, connection with natural spaces and community, reduced toxin exposure, and stress management. While mental health professionals and medical clinicians can emphasize personalized actionable lifestyle changes, not all modifications are accessible or possible to everyone. This is where advocacy for policy-making comes in, at the intersection of politics, ecology, and healthcare; human physiology is, in fact, dependent on the larger environment dictating the microbes that facilitate health and dis-ease.

Nutritional Disparities: Diets high in fiber and low in processed foods are associated with gut microbiota diversity and improved health outcomes. However, access to fresh, nutritional foods varies greatly across the United States, mediated by food insecurity and the historically oppressive origins of food deserts. Promoting universal access to healthy foods and nutritional education may help support microbiome equity. Because eating patterns can be tied to trauma and psychological wellbeing, social objectives may need to go beyond simply providing dietary resources.

Industrialization and Urbanization: Industrialization in agriculture has negatively impacted the microbial composition of soil, producing less nutrient-dense foods. Similarly, urbanization has led to a loss of interaction with environmental microbes through reduced access to natural settings. Decreased air and water quality expose individuals to harmful chemicals, while increased noise and light pollution affects biological rhythms. Poor housing conditions can also expose individuals to environmental toxins and mold. Addressing environmental quality (air, water, etc.) and substandard housing conditions may be a starting point for microbiome equity, and some researchers have suggested incorporating microbiome-inspired green infrastructure into urban planning.

Stress: Chronic stress is prevalent throughout lower socioeconomic status and marginalized communities. Lifestyle modifications like managing sleep, exercising, and practicing meditation have been shown to support microbiome health, yet these interventions are often challenging to achieve. Implementing stress reduction programs and encouraging community support systems may mitigate the negative impacts of stress on the microbiome. At a public policy level, supporting psychological and physical safety by increasing access to public transportation, healthcare, and improving environmental quality may decrease barriers to stress management.

Conclusion

The microbiome may be likened to a bridge between the social determinants of health and health inequities. While there is a lot of work needed to address health disparities, on both a precision medicine and policy level, we can start the conversation by recognizing the role of microorganisms in mediating the impact of social, political, and economic forces.

For more info, check out the Microbes and Social Equity working group!